Pennsylvania not alone when it comes to rejected mail-in ballots

State rejection rates vary depending on deadlines, flexibility in fixing errors

Pennsylvania saw 1,000 fewer mail-in ballots rejected in the April primary election even as the number of returned ballots leaped by 100,000 over the spring 2023 primary.

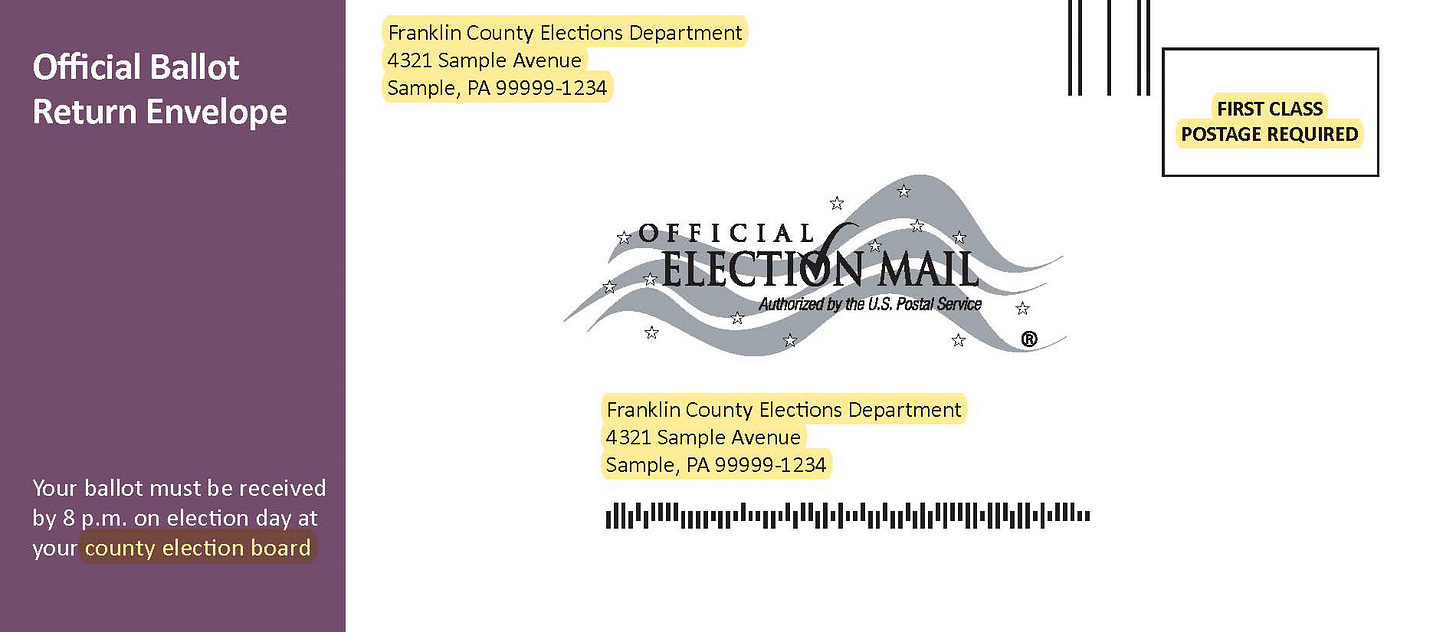

The lower rejection rate – 2.2% versus 2.7% for spring 2023 – comes as the Department of State unveiled uniform mail-in ballot materials designed to cut down on confusion by voters.

But don’t start popping champagne bottles.

The new look accounted for slightly more than half of the 15,928 rejected ballots, according to feedback the state received from counties.

Voters still forgot to use secrecy sleeves, sign their names or correctly date outer envelopes.

Pennsylvania is hardly alone when it comes to mail-in ballot rejections – or the lawsuits that abound over them.

A review of mail-in voting across the U.S. shows rejection rates are an inherent part of the process.

That’s largely because each step in filling out a ballot is error prone.

“Unfortunately, I think it’s probably not possible to reach zero rejection rates,” said Sarah Niebler, an associate professor in the political science department at Dickinson University.

What can make a difference is how willing a state is to allow voters to fix their mistakes or how flexible a state is with return deadlines.

“Election administration varies from county to county and state to state,” Niebler said.

Rejections cross state lines

A survey by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission found 36,268,524 people voted by mail in the 2022 general election. They represented about a third of all voters in that election. Of those who voted by mail, 1.5% or 549,824 saw their ballots discarded.

Nullification rates in that election – a midterm when just under half of all registered voters participated – varied with Arizona notching a 0.4% rate and California a 2.4% rate.

Pennsylvania’s rate was 1.9%, according to the EAC, an independent governmental agency that conducts election surveys every two years.

States posting the highest rejection rates tended to be those that only allow absentee voting for valid reasons such as being out of town on Election Day. They included Delaware (13.2%), Arkansas (6.8%) and Texas (3.4%).

Rejection rates also vary by county. Lehigh County posted a 2.3% rejection rate in spring 2023 while Northampton County’s rate was 4.3%, according to the Department of State.

Niebler said the overall rejection rate is small when compared to the 112,054,124 votes that counted in November 2022.

“However, I would say that one ballot rejected is one too many,” she said.

Rules run the gamut

Mail-in voting traces its roots to the Civil War when soldiers were given the right to vote from the battlefield, according to John C. Fortier, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington, D.C., think tank.

Absentee voting was later extended to people who were sick or away from home on Election Day.

The practice shifted in 1978 when California gave everyone the right to no-excuse absentee voting, now also known as no-excuse mail-in voting, Fortier said.

In all, 36 states and Washington, D.C., now allow mail-in voting with Pennsylvania joining the list in 2020 after a bipartisan group of legislators passed Act 77 the year before.

The other states include Colorado, where every registered voter automatically gets a mail-in ballot, and Hawaii, where voting is done primarily through the mail.

The remainder of the states permit absentee voting with a “valid” excuse. Pennsylvania still allows that option.

Rules for filling out ballots run the gamut.

Every state requires voters to sign their name and rejects mail-in or absentee ballots without them.

Some states such as Alaska and Oklahoma require that the voter’s signature be witnessed by another person who must also sign their name, according to a roundup of rules prepared by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Alabama and North Carolina mandate two witnesses or a notary republic. Mississippi requires absentee ballots to be signed by a notary or authorized public official.

In Ohio and Minnesota, voters must attest to their identity by listing a driver’s license number, state ID number or the last four digits of their Social Security number on ballot material.

Many states check signatures against those on record. They reject ballots outright if county election officials don’t think the voter’s signature doesn’t match the one on file.

That’s not the case in Pennsylvania.

In October 2020, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that ballots with signatures that don’t appear to match those on file cannot be rejected, according to an article by Spotlight PA. In the 7-0 decision, the court ruled Act 77 did not specifically allow rejections for that reason, thus counties could not exclude them.

Deadlines for receiving ballots also vary among the states, according to the National Conference or State Legislatures.

Most states, including Pennsylvania, require receipt of mail-in ballots by the close of polls on Election Day. Louisiana and North Dakota’s deadline is the day before Election Day.

Others are more lenient. Alaska counts ballots with proper postmarks if they are received within 10 days of an election. California’s window is seven days after an election.

Reasons for rejections

The reasons that ballots were rejected nationwide in the 2022 midterm mirrored Pennsylvania’s.

They lacked signatures, arrived late, were not placed in secrecy envelopes, were not sealed in official return envelopes or had errant markings on the ballots. Not having witnesses tripped up voters in states that require them as did mismatching signatures.

In Pennsylvania, an analysis of mail-in voting in spring 2023 by professor Niebler and Dickinson student Adam Mast found that Democrats outnumber Republicans in voting by mail. But rejections crossed party lines with both parties experiencing rejections at an equal rate.

Pennsylvania’s date requirement

In Pennsylvania, the Act 77 requirement that voters date their return envelopes has been one of the most vexing reasons related to rejections.

Like signatures, rejected voters forget to add dates. They also get dates completely wrong.

They write down their birth dates or the actual date of the election. They also have mixed up months or years.

Pennsylvania’s redesign tried to address the problem with colorful markings, bold-faced directions and the date partially filled in.

In addition, the Department of State sent a letter to counties urging them to count ballots that “can reasonably be interpreted to be ‘the day upon which [the voter] completed the declaration.’”

Though the actual number isn’t known, the date requirement still led to rejections in the April 23 primary.

In an effort to reduce date errors, on July 1, the Department of State sent a directive to counties that included instructions to use the full year — 2024 — in the area where voters fill in the date.

Though one may exist, Fortier and voting rights advocates contacted by Armchair Lehigh Valley said they are unaware of another state where a date requirement can lead to rejection.

Republicans have continued to support the requirement, saying dates are a part and parcel of legal documents where people must sign their names.

So far, their position has held up in ongoing court rulings, the latest happening in April when the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals declined to hear a lower-court ruling that kept the date requirement in place.

Dickinson’s Niebler said the date requirement is one of those rules that people who vote in person couldn’t make. While voters have to sign in, they don’t add a date by their names.

Fortier said voting in person affords other protections as well. He said the federal Help America Vote Act mandates that voting machines alert voters right away if they accidentally select two candidates for one open seat. Voters then can recast their vote.

Overall, Niebler said, voting at the polls is set up to avoid errors.

“What happens when you vote at the polls there are … poll workers whose responsibility it is to help make sure people vote successfully,” she said.

Curing part of a trend

Like Pennsylvania, Fortier said states have begun redesigning mail-in ballots to reduce errors.

He also said states are moving in the direction of allowing mail-in-ballot voters to fix or cure their mistakes.

A review by Ballotpedia found that 24 states in 2022 required county election offices to notify or make reasonable efforts to contact voters about missing signatures or signatures that didn’t match their voting records.

Some permit voters time to fix them beyond election day, including Illinois’s 14-day policy.

Pennsylvania’s Act 77 doesn’t address ballot curing. The silence led to a deadlocked state Supreme Court ruling in October 2022 that, in effect, left it up to counties to decide whether to let voters fix their ballots.

An analysis by Spotlight PA and VoteBeat found that at least a dozen counties, including Lehigh and Northampton, permit curing while nine, including Lancaster, forbid it.

Niebler said some Pennsylvania counties permit curing but don’t tell you if you made a mistake, leading to a situation where “you wouldn’t know to go try to cure it.”

Ari Mittleman is executive director of Keep Our Republic, a nonpartisan group that educates people about rules on the electoral process. His group was part of Niebler’s mail-in voting study.

Mittleman said much of Pennsylvania’s ballot rejections are linked to state law, which gives much of the power over how to conduct elections to counties, including whether to give latitude on dates as the state suggested.

“There is, for better or worse, a pretty long leash given to county governments,” he said.

Slew of lawsuits

In Pennsylvania, mail-in ballot issues have led to about a dozen federal and state lawsuits since 2020, with sometimes contradictory court decisions.

The parties include voting rights advocacy groups that want to count as many mail-in ballots as possible and Republicans seeking to end the practice altogether or make sure the letter of the law is followed.

In the latest lawsuits, advocacy groups are taking a new approach – suing counties that don’t notify voters or permit them to cure ballots with mistakes.

On July 1, seven voters and others filed a lawsuit against Washington County over its decision against alerting voters of mistakes. Previously, Washington let voters know.

The lawsuit followed a similar suit filed against Butler County in May. There the county allowed some voters to add missing signatures or dates on their mail-in ballot materials but did not allow at least two voters to file provisional ballots after they learned they forgot to put their ballots in the secrecy sleeves.

In arguing against allowing curing, Republicans have said it shouldn’t be permitted because it is not specifically addressed in Act 77.

“By inspecting the ballots and notifying voters about discovered defects, (Election) Boards are vastly exceeding their Authority,” Republican plaintiffs wrote in one brief.

Voting advocates disagree.

“Ballot curing is not changing your vote,” said Sarah Martik, executive director for the Center of Coalfield Justice in Washington and Greene counties. “Ballot curing allows individuals to correct simple administrative errors that could prevent their vote from being counted.”

The Department of State noted lawsuits over dates and signatures didn’t happen when Pennsylvania only permitted absentee voting – despite similar requirements on those ballots.

“It is only in recent years that non-material ballot requirements on a voter’s declaration have been weaponized to disenfranchise voters,” the state said in an email response to a question from Armchair Lehigh Valley.

Political observers link Republican-led lawsuits to former President Trump’s distrust of mail-in voting following his 2020 loss. In Pennsylvania, he was ahead until mail-in ballots were added and gave now President Joe Biden the win.

While Trump’s opinion has changed, the Republican National Committee has continued to file suits, including one in Nevada over late-arriving ballots, according to The Associated Press.

Education and practice

Pennsylvania’s Department of State said it was encouraged by what it calculated as a 10% reduction in rejections thanks to the ballot redesign.

In an email exchange, the Department said it will continue to look for ways to reduce rejections.

“The Shapiro Administration is committed to ensuring that voters are not disenfranchised for technicalities that have no impact on election integrity and security,” the Department said.

Niebler said education is key.

“I’m wholly supportive of continuing to educate the public and trying to reduce and eliminate the hurdles voters face when voting by mail (and in person!),” she said in an email.

Mittleman, a 2001 Parkland High School graduate, has faith that rejection rates in Pennsylvania will fall.

As people continue to use mail-in voting, he said, they will get used to the process and make fewer mistakes.

“It’s kind of like you live, you learn,” he said.

Robert H. Orenstein contributed to this report.

This story has been updated to reflect that the State Department sent a directive dated July 1 to county Boards of Elections asking that the full year — 2024 — be included in the date section on the return envelope. The state did not disclose the directive in a July 2 email sent to Armchair Lehigh Valley in response to questions, including whether there were any plans to tweak the date section.